How to balance chemical equations

Chemistry students often struggle with balancing chemical equations, but these tips will make this vital skill easier to master

Is there an easy way to balance chemical equations?

I get asked this a lot by students wanting help with this notoriously difficult skill. What students want to know is, is there are a set of rules or step-by-step process to follow that, once learned, will allow you to balance even the hardest equation?

The answer is yes, there is a method but unfortunately, it’s a mathematical method that uses algebra to find the balancing numbers, so it’s not that suitable for less mathematically-inclined chemistry students.

So, what are the other options?

If you’re a GCSE, A Level or IB student, you can learn the ‘balancing by inspection’ method, which is one of four methods used to balance chemical equations. (The other three methods – redox balancing, algebraic balancing, and simple algebraic balancing – I will cover in other blogs.)

What is balancing chemical equations by inspection?

‘By inspection’ suggests some magical process where you stare long and hard at the equation and the balancing numbers mysteriously float into your head. That’s pretty much what happens when you’ve been balancing equations for a long time.

Before you get to that point, the good news is this method can be reduced to a set of rules that, once mastered and practised, will equip you with Jedi balancing skills allowing you to deal with 95% of chemical equations you are likely to meet (the other 5% are either so difficult you can only use mathematical methods, or you have to use the redox balancing method).

Principles behind balancing chemical equations

Let’s first state the key principles behind balancing chemical equations:

1. You cannot destroy atoms

The total number of atoms on each side of the equation must be the same. The number of atoms of each element must therefore be the same on each side of the equation.

2. You cannot destroy charges

The total number of charges must be the same on both sides of the equation. Charges are particles, so a different number on each side of the equation means some matter has been destroyed. Not allowed.

These first two principles are based on the Conservation of Matter. The other principle you mustn’t violate is:

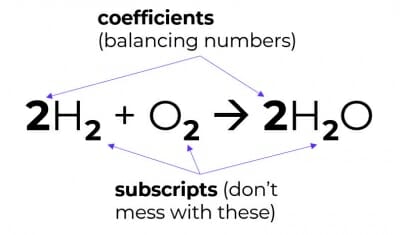

3. You cannot change chemical formulae

Meaning, you may only balance equations by changing coefficients (i.e. the balancing numbers), not by changing subscripts.

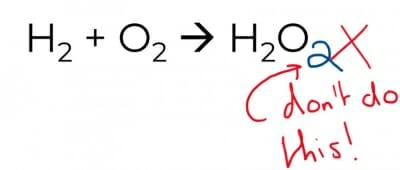

Changing the subscripts changes the compound into something else – that would be alchemy, not chemistry.

The above approach is certainly cunning but there is a very big difference between H2O and H2O2!

Tricks to balance chemical equations

With those basics out of the way, let’s have a look at the rules that collectively make up the ‘balancing by inspection’ method. These rules are shown in action in the worked examples below.

Rule 1: Look for an element that appears only once on the LHS and RHS

In other words, avoid elements present in more than one compound to begin with. Why? Because if an element appears in more than one compound, each compound will need a coefficient that will potentially unbalance other elements. It’s not a good idea to start out your balancing by creating imbalances.

If you’re unlucky and there isn’t an element that only appears once on each side, start with the one present in the fewest compounds

Rule 2: Try subscripts as balancing numbers

Often, an element (or ion’s) subscript on one side of the equation will be its coefficient on the other side.

This is the single most useful trick to remember. After working through over 350 equations to see which rules are most used (I need to get out more!), I estimate you will use this trick to balance 90% of equations.

You can’t change subscripts so use them instead.

Rule 3: Look for forced coefficients

If an element or ion appears only once on each side of the equation and is already balanced, its coefficient on both sides must be the same

This rule also applies to polyatomic ions (e.g. SO42-, NO3–, CO32-, PO43- etc.)

Rule 4: Don’t start with compounds containing many elements

Usually, you should try to balance compounds that contain as few elements as possible first

Changing a coefficient in front of a compound containing three elements will potentially balance one element and unbalance two. You are likely to be making life difficult for yourself. This rule is about keeping it simple. Of course, in some equations applying the earlier rules will need you to break this one.

Rule 5: Remember you can use fractions

Coefficients can be fractions and they are useful for correcting odd/even imbalances and adding single elements

Rule 6: Sum of charges LHS = sum of charges RHS

Correct negative charge imbalances using electrons.

Rule 7: Balance water later

Unless the earlier rules force you to, don’t start with water

Water is a very common substance in a chemical reaction and oxygen and hydrogen are very common elements. Any number you put in front of water will change oxygen and hydrogen, forcing you to use another coefficient to balance those elements in other compounds.

The exception to this rule is when hydrogen or oxygen have a subscript on one side of the equation that you must use as the coefficient on the other side.

Worked examples

Example 1

_Cl2 + _KBr → _KCl + _Br2

- Don’t start with KBr or KCl (rule 4)

- Use the subscripts from Cl and Br (rule 2) and it’s balanced:

Cl2 + 2KBr → 2KCl + Br2

Example 2

_N2 + _H2 → _NH3

- Equations where an element has an odd number of atoms on one side and an even number the other are common

- Here, there are 3 H’s on the RHS and 2 on the LHS

- Use rule 2 and swap the subscripts for H by putting 3 in front of H2 and 2 in front of NH3

N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3

Example 3

_C2H5OH + _O2 → _CO2 + _H2O

- Don’t start with ethanol, C2H5OH (rule 4) – change this, you are going to change the number of C, H and O atoms

- Instead, use C’s subscript (rule 2) and put it in front of CO2.

C2H5OH +_O2 → 2CO2 + _H2O

- The rest is just counting atoms. Notice there are 6 H’s in ethanol and only 2 in water? We can correct that with a 3 in front of water.

C2H5OH +_O2 → 2CO2 + 3H2O

- Lastly, count and correct the oxygen atoms with a 3 in front of O2

C2H5OH +3O2 → 2CO2 + 3H2O

Example 4

_OH– → _H2O + _O2 + _e–

- First of all, use H’s subscript as the coefficient for OH– (rule 2):

2OH– → H2O + _O2 + _e–

- We can sort out oxygen by halving O2 (rule 5):

2OH– → H2O + 1/2O2 + _e–

- Lastly, balance the charges (which are currently -2 on the LHS and -1 on the RHS) by putting a 2 in front of e– (rule 6):

2OH– → H2O + 1/2 O2 + 2e–

- This is now balanced, but if you’re one of those students that doesn’t like fractions in chemical equations, or the question asks for whole number coefficients, just multiply by the denominator (i.e. double everything):

4OH– → 2H2O + O2 + 4e–

Example 5

_Fe2O3 + _CO → _Fe + _CO2

- If you don’t spot the trick you have to use for this one, you can end up going around in circles. The trouble with this one arises because you have 3 O’s on the LHS and 2 O’s on the right and O in CO.

- You certainly don’t want to start with Fe2O3 first (rule 4)

- If it were not for CO containing oxygen, using rule 2 to swap oxygen’s coefficients (2Fe2O3 and 3CO2) would be a great way to balance oxygen, then you could just balance iron with a 4:

2Fe2O3 + _CO → 4Fe + 3CO2

- But now you’re stuck. You’d be forced to put a 3 in front of CO to balance carbon, unbalancing oxygen in the process.

- Instead, make the logical move and use rule 2 to balance iron:

Fe2O3 + _CO → 2Fe + _CO2

- Now use the ‘forced coefficients’ rule 3.

- CO and CO2 are the only compounds containing carbon, and carbon is already balanced (there is one atom in each compound containing it on each side). This means the coefficient in front of CO and CO2 must be the same.

- To find it, you could use trial and error (e.g. try 1, 2, 3 and so on until carbon and oxygen are balanced) or solve it with simple algebra

- If we let x = the coefficient for CO and CO2, we can write a rule for the total number of oxygen atoms on the LHS and RHS:

Fe2O3 + xCO → 2Fe + xCO2

3 + x = 2x

Hence x = 3

Fe2O3 + 3CO → 2Fe + 3CO2

Example 6

_HNO3 + _CaCO3 → _Ca(NO3)2 + _CO2 + _H2O

- Certainly I would not start with HNO3 or Ca(NO3)2 because you’re going to upset too many elements changing those coefficients (rule 4)

- Don’t start with H2O either because oxygen is present in every other compound (rule 7)

- Instead, we’ll use the forced coefficient rule again (rule 3), this time applied to a polyatomic ion, NO3–

- NO3– is a spectator ion in this equation, meaning it doesn’t participate in the reaction at all. All the NO3– ions on the reactant side get transferred to the product side with no change. What that means is the N and O atoms it contains are stuck together and can be treated the same way you’d treat an atom

- We can therefore use rule 2 and use the NO3– subscript from the RHS to balance HNO3 on the LHS:

2HNO3 + _CaCO3 → _Ca(NO3)2 + _CO2 + _H2O

- This now forces the coefficients for CaCO3, CO2 and H2O to be 1. The equation is now balanced.

2HNO3 + CaCO3 → Ca(NO3)2 + CO2 + H2O

Example 7

_Na2SnO3 + _H2S → _SnS2 + _NaOH + _H2O

- This looks tricky but the above rules will help smash it

- Always scan an equation that has lots of elements to see if you can apply rule 1

- For this equation, we can apply it to Na, Sn and S as these are the elements that only appear in one compound on each side

- On the LHS, Sn is tied up with Na and O so changing Na2SnO3‘s coefficient is a bad idea because you’ll change all those elements on the RHS too

- The smart move is use rule 2 twice: use Na’s subscript on the LHS to balance NaOH (which sets the coefficient for Na2SnO3 as 1) and S’s subscript to balance H2S on the LHS (which sets the coefficient for SnS2 as also 1):

Na2SnO3 + 2H2S → SnS2 + 2NaOH + _H2O

- Now all that remains is to correct H and O, which conveniently turned out to be already balanced:

Na2SnO3 + 2H2S → SnS2 + 2NaOH + H2O

Example 8

_Hg(OH)2 + _H3PO4 → _Hg3(PO4)2 + _H2O

- As ever, we avoid messing with compounds containing lots of elements unless we’re forced to (rule 4) and hunt for an element that only appears once on each side (rule 1)

- Turns out it’s Hg, and since it appears only once we have no choice other than to use its RHS subscript as its coefficient on the LHS (rule 2)

3Hg(OH)2 + _H3PO4 → Hg3(PO4)2 + _H2O

- We then apply rule 2 again, this time to the PO43- ion:

3Hg(OH)2 + 2H3PO4 → Hg3(PO4)2 + _H2O

- Counting up, there are 12 H’s on the LHS and none on the RHS currently, and we’re also short of 6 O’s on the RHS. A 6 in front of H2O now balances this equation (rule 7, using water last to to correct H’s and O’s):

3Hg(OH)2 + 2H3PO4 → Hg3(PO4)2 + 6H2O

Example 9

_(NH4)3AsS4 + _HCl → _As2S5 + _H2S + _NH4Cl

- Well, this looks awful!

- We avoid the complicated-looking compounds first (rule 4) and note that As appears only once on each side of the equation (rule 1)

- Since we can’t change its subscript on the RHS, let’s use it on the LHS (rule 2). In doing so, we will also set the coefficient for As2S5 as 1:

2(NH4)3AsS4 + _HCl → As2S5 + _H2S + _NH4Cl

- Because S has a 4 subscript, that 2 coefficient has multiplied up the number of S atoms on the LHS to 8. We have 5 on the RHS in As2H5, so we’re short 3. To fix that, put a 3 in front of H2S:

2(NH4)3AsS4 + _HCl → As2S5 + 3H2S + 6NH4Cl

- NH4+ is a polyatomic ion and that 2 we just used as a coefficient has also created 6 of them on the LHS because of its 3 subscript. This forces us to put a 6 in front of NH4Cl…

2(NH4)3AsS4 + _HCl → As2S5 + 3H2S + 6NH4Cl

- …and that 6 means we must now put a 6 in front of HCl to balance Cl and complete the equation:

2(NH4)3AsS4 + 6HCl → As2S5 + 3H2S + 6NH4Cl

Example 10

_MnO4– + _H+ + _Fe2+ → _Mn2+ + _Fe3+ + _H2O

- Oh hell, this looks like a lot of fun. This one is firmly in A Level / IB Diploma territory and you’d ordinarily use the redox balancing method

- Let’s try to sort it out without that though…

- The first thing to note is that Fe is already balanced, because it only appears by itself once on each side of the equation. That means the coefficient for Fe must be the same on both sides (rule 3). We don’t know what that number is yet, but it’s got to be the same for Fe2+ and Fe3+.

- The logical first move is use O’s subscript on the LHS to balance it on the RHS (rule 2 again, and we violate rule 7 by changing H2O first here but hey, this one’s tough…)

MnO4– + _H+ + _Fe2+ → Mn2+ + _Fe3+ + 4H2O

- Note we’ve also set the coefficients for Mn and Mn2+ to 1 by making that change, so we can’t now change those

- The 4 in front of water means we have to put an 8 in front of H+, and now the equation is balanced in terms of elements but not charge

MnO4– + 8H+ + _Fe2+ → Mn2+ + _Fe3+ + 4H2O

- We now need to use rule 6 to find the missing coefficient, which we can do using simple algebra (or trial-and-error if you hate maths):

- Let x = the coefficient for Fe2+ and Fe3+

MnO4– + 8H+ + xFe2+ → Mn2+ + xFe3+ + 4H2O

- Since total charges LHS = total charges RHS, we can write:

-1 + 8 + 2x = 2 + 3x

7 + 2x = 2 + 3x

x = 5

- Finally, it’s balanced:

MnO4– + 8H+ + 5Fe2+ → Mn2+ + 5Fe3+ + 4H2O

The importance of practise

As I’ve stressed repeatedly, balancing chemical equations is a skill that takes lots of practise to master.

Here are the rules summarised:

- Rule 1: Look for an element that appears only once on the LHS and RHS

- Rule 2: Try subscripts as balancing numbers

- Rule 3: Look for forced coefficients

- Rule 4: Don’t start with compounds containing many elements

- Rule 5: Remember you can use fractions

- Rule 6: Sum of charges LHS = sum of charges RHS

- Rule 7: Balance water later

The above set of rules is not a checklist; you are never likely to use all of these tricks to balance an equation and some won’t apply to certain equations. The only way you will get better at quickly selecting the right rule to apply is by practising lots of balancing equations.

Finally, be aware that appearances can be deceptive. Simple-looking equations can be fiendishly difficult. Ones with many elements and complicated-looking compounds can turn out to be easy.

With that in mind, here are some practise questions for KS3/GCSE level and A Level / IB Diploma, complete with answers. Some are extremely easy to balance and only need one rule, others are much more difficult.

Good luck!

[…] is the starting point but you’ll have to use other rules to complete the balancing. (I wrote a longer post about the balancing chemical equations that you might want to check […]

[…] If you learn it, it can be a very fast way to balance difficult equations that are hard to balance by inspection, but there is no formal requirement to learn this method, nor should you ever be required to […]

[…] my last blog, I covered seven rules you can use to balance chemical equations, which make up the ‘balancing by inspection’ method. This time, we’re looking at redox […]